Pineapple ice cream: a potted history and some English 18th-century recipes

Confectionery shops in 18th-century England and Europe were a far remove from modern sweetshops. In addition to selling (or hiring out) expensive porcelain and glass tableware, they sold fresh fruit, like pineapples and strawberries, and luxury sugar-based sweet treats made on the premises, for a wealthy clientele. These typically included biscuits, wafers, highly decorated Twelfth Cakes, sweeties like sugar plums (what we now call sugared almonds), preserved peels and jams, as well as jellies and whip syllabubs that could be eaten on the spot or taken home.

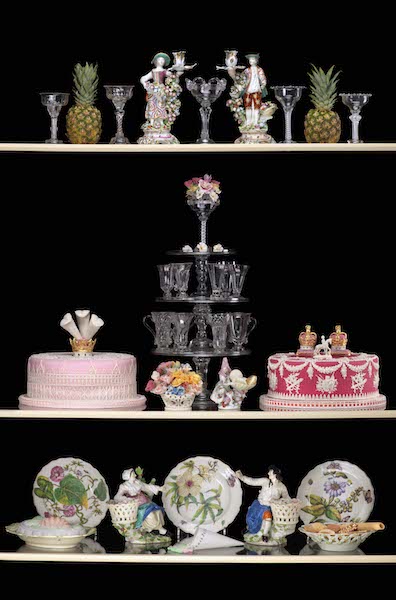

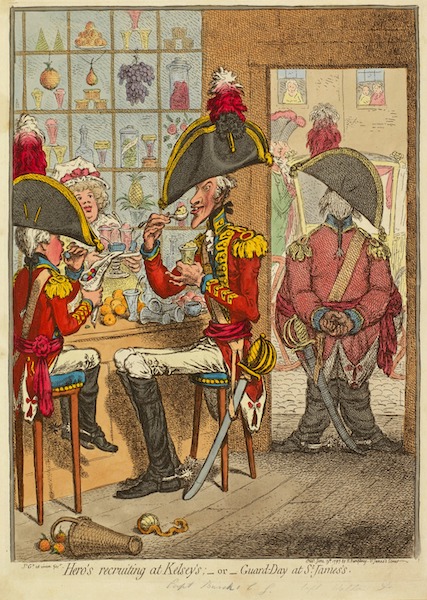

The sheer variety of food and tableware sold by high-end confectioners can be seen in the recreation of a late 18th-century confectioner’s window, which Ivan Day conjured up for us in the Feast & Fast exhibition. It was inspired in part by satirical artist James Gillray’s cartoon of June 1797 showing soldiers eating sweet treats inside a London confectioner’s, also on display in the exhibition.

According to Ivan, ice cream – or ‘ice’ in 18th-century parlance – was the most elite refreshment that these confectioners made, and it came in a huge variety of flavours. Prices varied according to the cost of the ingredients. Ices made from common garden fruits were less expensive than those made from luxury fruit such as the pineapple. In 1764, according to his trade card (now in The British Museum), the Bond Street confectioner Thomas Street sold a pint of strawberry ice for 3 shillings and 9 pence, while the same quantity of pineapple ice cream cost more than double the price, at 7 shillings and 6 pence.

Like many confectioners, Street also sold fruit-flavoured ices moulded in the form of the fruit, using fruit-shaped pewter moulds supplied by pewterers such as Thomas Chamberlain of Greek Street, London. The most common 18th-century mould for making an ice cream pineapple was designed to replicate the pine-cone-shaped body of the fruit without any leaves. When the frozen ice was removed from the mould, real leaves salvaged from the fruit, were attached to the top, making a very convincing ‘pineapple in ice’. You can find out more about how these were made in this article.

As far as Ivan knows, the earliest published recipe for pineapple ice cream is in French: it appeared in Emy, L’Art de Bien faire Les Glaces d’Office (Paris, 1768). Recipes in other languages quickly followed.

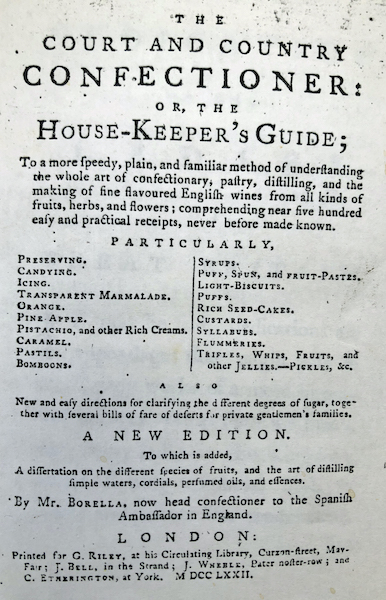

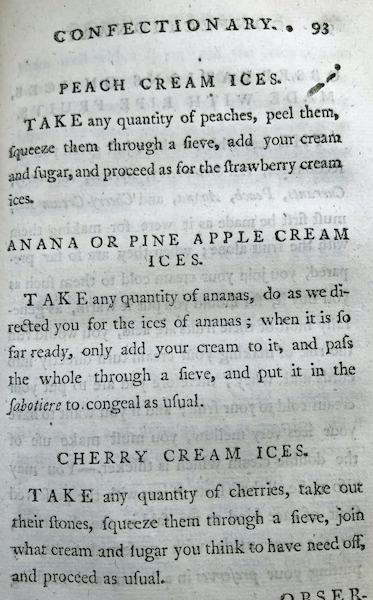

In 1770, recipes for both pineapple water ice (‘Anana, or pine apple ice’, pp. 84-85) and pineapple ice cream (‘Anana or pine apple cream ices’, p. 93) were published in English in The Court and Country Confectioner (London, 1770). The first edition of this highly influential book on the subject of confectionery was launched anonymously, but in a later edition of 1772, the author is identified on the title page as ‘Mr. Borella, now head confectioner to the Spanish Ambassador in England’.

The other English recipe to be published hot on the heels of Emy and Borella was by Frederick Nutt in The Complete Confectioner (London, 1789).

As the title-page reveals, Nutt had been apprenticed ‘to the well-known Messers. Negri and Witten of Berkley-Square’. These were the successors of another Italian immigrant, Domenico Negri from Turin, who had established ‘The Pot and Pineapple’, a fashionable confectionery shop in Berkeley Square, London, which he ran with his English wife, Ann Gunter. By the early 19th-century, this establishment was known as ‘Gunter’s’, but was still popularly referred to as ‘The Pineapple’. Ivan’s early 19th-century pewter sorbetiere for mixing ice cream (also exhibited in Feast & Fast together with the pineapple ice cream mould and a spaddle) is from Gunter’s, and may well have been used in the production of pineapple ice cream, as well as other luxury fruit ices.

Ivan told me,

“Although we cheated with industrially-produced mango ice cream through necessity when we recreated our 18th-century ‘pineapple in ice’ for the Feast & Fast photo shoot, I have made all of these pineapple ices using 18th-century equipment. Unfortunately, they do not really lend themselves to the modern kitchen as the freezing process was entirely different, but I have got them all to work well.”

With great thanks to Ivan Day for his help with this text.

Victoria Avery, Keeper of Applied Arts and Co-Curator of Feast and Fast