Behind the Scenes: Recreating an 18th-century pineapple ice cream

‘We love the pineapple ice cream image on the lamp-post banners and posters advertising the Feast & Fast exhibition. Why did you choose it for the show’s logo, and how did you make it?’

I’ve been asked this question so many times since Feast & Fast opened in late November, and now we’re closed, I thought it time to let you in ‘behind the scenes’ and into a few secrets!

We chose the pineapple as the logo for Feast & Fast for several reasons. Since the 19th century, the pineapple has come to represent friendship, hospitality and welcome, which are great messages for the Museum. It’s also a fantastic ‘icon’ from a designer’s point of view as it has such a distinctive shape and profile, and such a vibrant yet simple colour: bright yellow for the body of the fruit, and rich green for its crowning leaves. All-in-all, quite unmistakable. This may be why the Museum’s front railings are composed of flourishing pineapple plants: green stems and leaves with vibrant gilded pineapples acting as flamboyant finials.

More specifically, the pineapple is a key motif in the exhibition, given that it was our founder’s grandfather, Matthew Decker, who grew England’s first crop of pineapples in his garden in Richmond-upon-Thames in the early 18th century. The pick of Decker’s crop was recorded in this marvellously quirky portrait of 1720, which is now in The Fitz.

This huge horticultural feat that was publicised in 1721 by Richard Bradley, who became the first Professor of Botany at the University of Cambridge a few years later.

To celebrate Decker’s botanical achievement, his links with Bradley and Cambridge, and 300 years of pineapple growing in Britain, we thought it would be fun to make the pineapple a feature outside of the museum to welcome visitors in. So we commissioned artists Sam Bompas and Harry Parr to create a fun, funky, family-friendly and frankly unmissable giant pineapple for The Fitz’s front lawn. It’s lit up at night and since the outbreak of Covid-19 and the Museum’s closure, it’s become a resolute beacon of hope and has been nicknamed The Pineapple of Positivity.

And this is why we also used the pineapple logo on the eye-catching and memorable posters and lamp-post banners advertising Feast & Fast. Keen to keep food, its production and presentation, and the multi-sensory aspects of the exhibition at the heart of our publicity for it, we thought that a pineapple ice cream would be ideal. After all, who doesn’t like ice cream?

This is when we approached our food consultant, Ivan Day, for his expert help. From his half-century worth of experience in such matters, Ivan advised us not to photograph a replica pineapple-shaped ice cream, moulded in silicon or plastic, as they never look real. “You must make a real ice cream from a genuine 18th-century pewter mould, and place it on a genuine 18th-century glass salver that has been frozen overnight so it is really cold. And you must photograph it immediately, so it is really crisp and still glistening. But, be warned, the ice cream will start melting after only a few seconds, so you’ll have to be really quick, or the photographers will end up with the green crown floating in a yellow puddle!” No pressure then…

Ivan generously offered to let us use his late 18th-century hinged tripartite pewter pineapple-shaped mould for the purposes together with his early 18th-century glass salver, and gave us permission to deep-freeze both overnight.

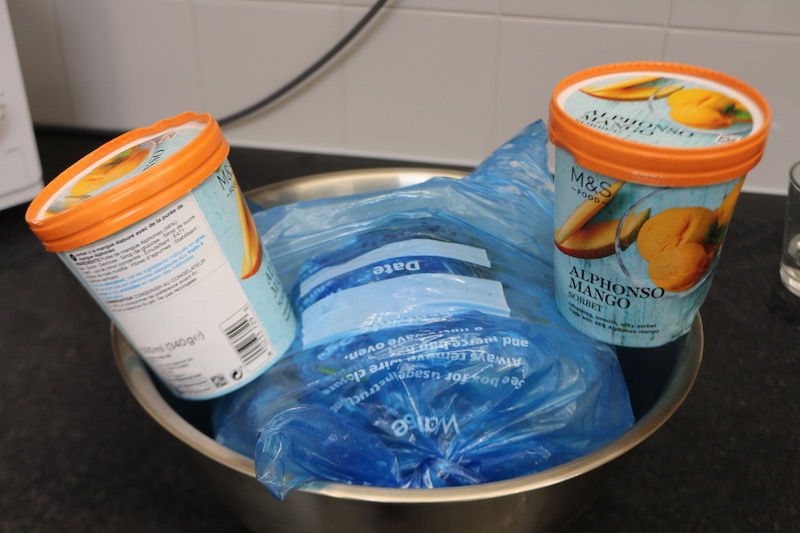

Being very short of time, we sadly couldn’t make any pineapple ice cream ourselves, so on Ivan’s advice I bought some mango sorbet instead, as it’s similar in colour. I also got some salt, ice cubes, cocktail sticks, and a fresh pineapple with a good-looking crown of leaves.

After storing the ice cream mould and salver overnight in the Museum café’s freezer (with grateful thanks to the Tate catering team!), we were good to go.

Here is a photo record and instructions of how we did it. (If we ever do this again, we would avoid doing it on a scorching hot day in mid-June!)

Step 1: vigorously mix salt and ice into the sorbet to stop it from melting so quickly once solidified.

Step 2: carefully spoon the ‘pineapple ice cream’ into all three sections of the open mould

Step 3: carry on until the mould is completely full

Step 4: carefully close the mould and put it into the freezer to solidify overnight

Step 5: next morning, take a fresh pineapple and carefully saw its crown of leaves off

Step 6: take 3 toothpicks and carefully push them halfway into the stump of the crown

Step 7: retrieve the frozen ice cream mould and glass salver from the freezer and open the mould, using a teacloth to protect your hands from ice-burn!

Step 8: carefully saw a small slice off the top of your ice cream so that it’s flat

Step 9: quickly place your ice cream centrally on the frozen salver, and carefully push the crown on top, making sure the ends of the toothpicks engage with the ice cream

Step 10: run the ice cream and salver into the photography studio without dropping it, again using the teacloth to protect your hands from ice burn and carefully place on the table

Step 11: Let the photographer get on with her task before the ice cream melts!

Step 12: rescue the melting pineapple before it runs everywhere and makes a huge mess, and let the photographer have her rightful reward!

Through her skill and expertise, Katie Young, one of the Museum’s superb in-house photographers, was able to capture some wonderful images of the pineapple ice cream alone, and also with the 18th-century equipment that was typically used to make it by professional confectioners. These were used in the exhibition catalogue, on the website and for publicity.

And that’s the end of my story!

With many thanks to Ivan Day, Gillie Whitehead, Katie Young, Luke Syson, and Tate Catering.

Victoria Avery, Keeper of Applied Arts and Co-Curator of Feast and Fast