‘To eat or not to eat’: The early modern history of dairy and meat alternatives

The use of dairy alternatives, such as almond milk, is not a modern phenomenon but is firmly embedded in early modern food choices. While food choices were to a large extent determined by seasonal availability and economic means, religion also played a vital role in determining what people living in Europe between 1500 and 1800 ate. The calendar year was made up of single fast days as well as longer periods of abstinence, which prohibited the eating of meat and dairy products – Fridays, Saturdays, and some Wednesdays as well as Advent and Lent – totalling a staggering 40% of the year. Fasting days were often called ‘thin days’ or ‘fish days’ due to the fact that so much fish was eaten as a meat substitute. That said, the actual extent to which these religious rules were observed is questionable. We know that practice does not always follow prescription: dairy-loving Christians could buy dispensations from the Church, known as ‘butter indulgences’, which allowed them to eat dairy produce during Lent.

For most people, however, food on ‘thin’ days, as opposed to ‘fat’ days when there were no food restrictions, was dominated by vegetables, pulses, nuts, as well as seafood and fish, as seen in van der Heyden’s Thin Kitchen (fig. 1), in which a group of scrawny, impoverished and famished people fight over a pot of mussels and root vegetables. The bread is so stale and hard that it has been abandoned with the carving knife irretrievably jammed inside, and the stock fish is so tough that is has to be broken into pieces with a hammer. A well-fed man at the door tries to escape this bleak scene of culinary deprivation and desperation.

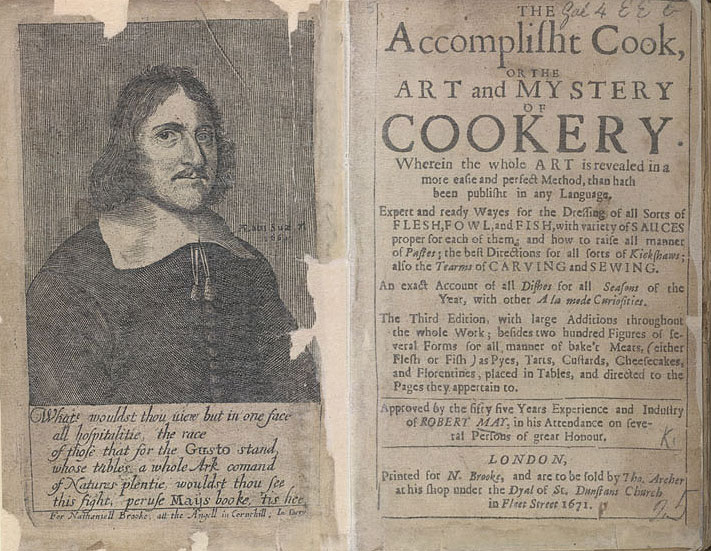

Finding dairy and meat alternatives was essential to meet the culinary requirements of ‘thin days’ and make them tolerable. Recipes books in Protestant and Catholic countries provided elaborate and multi-course vegetarian menus for ‘thin’ days, many of which did not contain any dairy or animal products. In The Modern Steward of 1694, the Neapolitan Antonio Latini described a lunch menu for some aristocratic patrons, which included a macaroni dish prepared with almond and pine nut milk, followed by a swordfish dish ingeniously made to look like ‘chops’. A generation earlier, the English Catholic cook, Robert May, published ‘A bill Fare formerly used in Fasting days, in Lent’ in his Accomplisht Cook of 1660 (fig. 2). The lack of meat was more than made up for by the sheer quantity and different types of fish and seafood (including oysters, eels, pike, carp, lobster, ling, haddock, sole, cod, and scallops) as well as the astonishing variety of ways to prepare them.

It was this rich history of cooking without dairy or meat products that inspired the early religious radical and animal-rights activist Thomas Tryon to promote his own vegetarian regime. In a remarkable series of self-help books, such as Wisdom’s dictates of 1691, he included 75 recipes for dishes ‘easily procured without Flesh and Blood, or the Dying groans of God’s innocent and harmless Creatures, which do as far exceed those made of Flesh and Fish’. While the roots of Tryon’s vegetarianism lay in earlier Christian practice, his concern for animal welfare and his criticism of the ‘dark side’ of the dairy industry appear entirely modern and relevant to today.