Eating Italian before Elizabeth David

The cookery writer Elizabeth David famously told readers of her first book, A Book of Mediterranean Food (1950), that they would only find olive oil in pharmacies as it was commonly used as a remedy for blocked ears. In fact, olive oil together with many other Italian food products have a much longer history in Britain, the result of cultural and culinary exchange with Europe from antiquity onwards. In the 16th and 17th centuries, young British men who travelled to Italy – for example, Padua to study medicine or Rome to visit Classical ruins – acquired a taste for all things Italian, including fashionable clothes (such as perfumed gloves) and fashionable foods (such as salad).

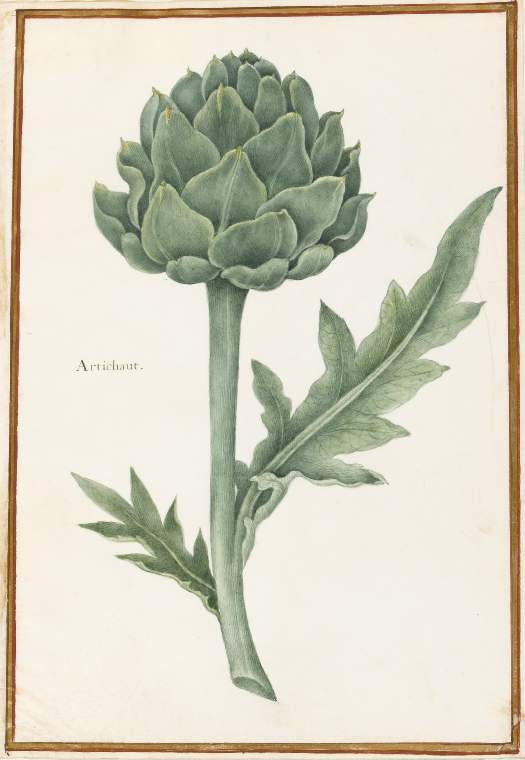

Giacomo Castelvetro, an Italian who first went England in 1580, having converted to Protestantism, introduced his aristocratic students to Italian food by means of his ‘Brief account of all of the roots, herbs, and fruit, cooked and raw, which are eaten in Italy’. Designed as a teaching tool, it included a discussion of all kinds of vegetables and fruits eaten in Italy, which were becoming increasingly popular in Britain, such as artichokes, objects of fascination for their usual shape and unique taste (fig. 1). By the 18th century, vegetables such as artichokes and asparagus had lost their exotic connotations and were being merrily boiled and pickled by English country housewives as if they had been native cauliflowers and cabbages. In The Country Housewife and Lady’s Director of 1736, Richard Bradley, the first Professor of Botany in Cambridge, included instructions for pickling and drying artichokes harvested in the summer ‘for winter use’ in warming stews.

Many staples of Italian cuisine, such as olive oil and Parmesan, had been enjoyed by English elites from the late 16th century onwards; and were readily available from Italian grocers in London by the early 18th century. Most famously, the cargo of the British merchant ship Westmorland, captured in 1778 by the French on its way home from Italy, contained no less than 32 wheels of Parmesan cheese. In August 1783, the Welsh painter Thomas Jones, who had been living in Naples for 3 years, ordered 24 pounds of macaroni and 5 pounds of cheese ‘for the macaroni’ to keep him and his family fed on their voyage home. While travel from Britain to Italy offered important cultural and culinary opportunities to privileged Grand Tourists, it also confirmed what the British thought about the Italians, national stereotypes based on perceived differences between Protestants and Catholics.

The notion of the ‘macaroni man’ developed from such stereotypes to mean a Briton who was effeminate, fashion-conscious, and well-travelled – a kind of fop or dandy of the 1760s and 1770s. They were often caricatured as elegantly dressed ‘mincing’ gentlemen, as in Darly’s tongue-in-cheek portrait of the Whig politician, Augustus Henry FitzRoy, 3rd Duke of Grafton, whose love of horses and racing explains his title as ‘The Turf Macaroni’ (fig. 2). While ‘macaroni men’ were defined primarily by what they wore and how they comported themselves rather than by what they ate, food was intrinsically linked to their name. Such a caricature emphasised the link in early modern food culture between eating certain foods and the corruption of the body. Cultural identities were understood to be especially fluid and they could be determined by what a person ate. To ‘protect’ one’s body from undesirable foreign influences, early modern guidebooks often offered advice to British travellers on the Grand Tour in Italy as to how to avoid the worst of Italian food, and where to find roast beef, which was the food above all others that had come to symbolise Englishness.

Despite xenophobic culinary attitudes and notions of cultural superiority based on national dishes, Italian food eventually found its way into British homes. Hannah Glasse, the most renowned of English cookery writers, provided a recipe, in The art of cookery made plain and easy of 1747, for ‘Vermicella’, encouraging her readers to make the pasta at home as it ‘far exceeds what comes from abroad being fresher’. Elizabeth David’s efforts in the 1950s to encourage the British public to eat like Italians was not, in fact, new but rather a revival of a longstanding love affair of the British with Italian food.