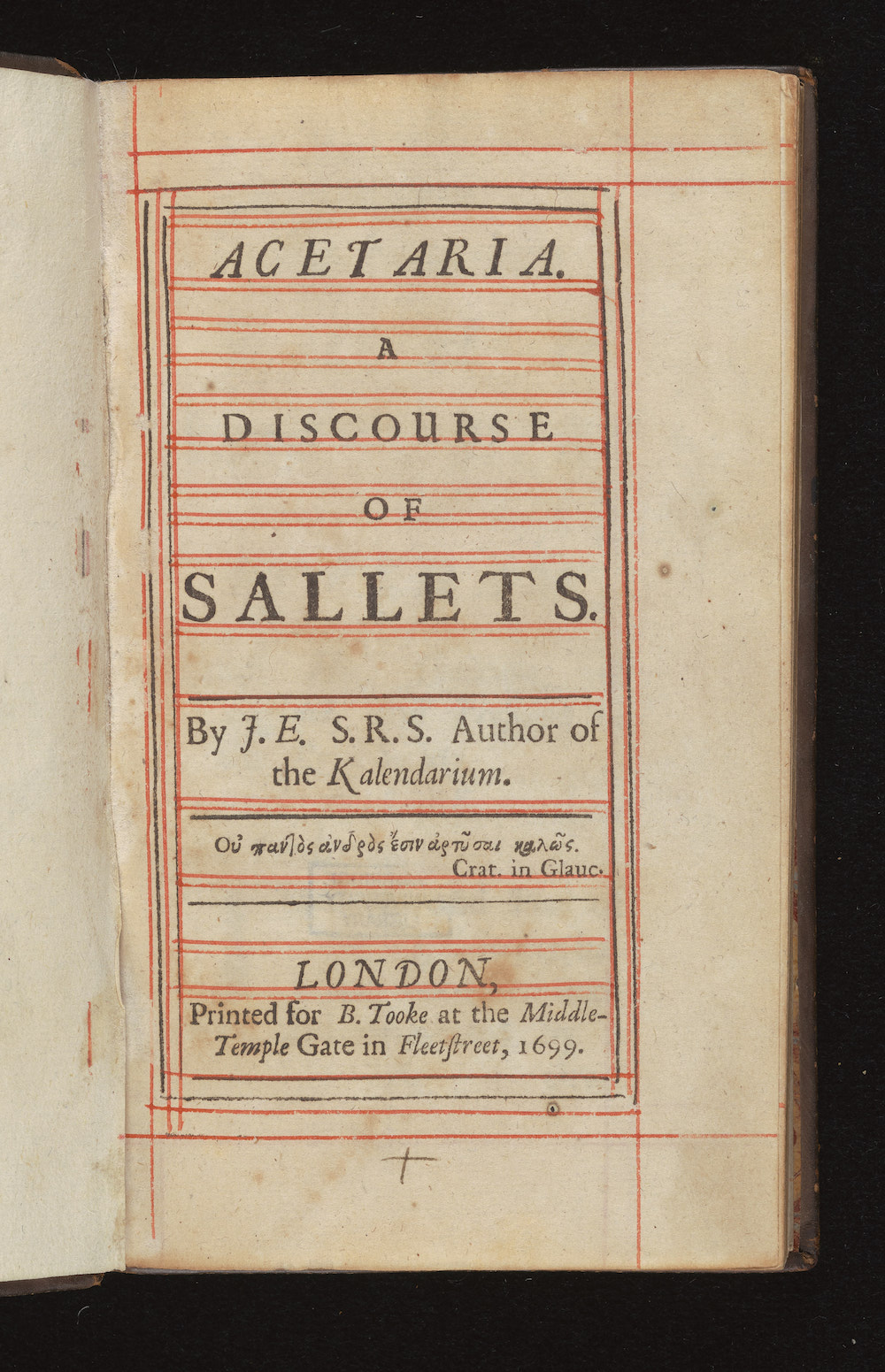

Acetaria: John Evelyn’s 1699 homage to salads and his 9-step guide to the perfect salad

The government official, diarist, and collector, Samuel Pepys, had five cookery books in his library. One of these – Acetaria: A discourse on sallets (1699) – was by his friend, the writer and naturalist, John Evelyn. Evelyn and Pepys were part of the same friendship circle which had been influenced by new writings on vegetables, inspired by the Classical world as well as by new culinary fashions from France, which abandoned the strong contrasts typical of Renaissance cooking in favour of more ‘natural’ and delicate tastes. This preference for simpler cooking promoted the use of vegetables that could be enjoyed by themselves for their own taste. It even extended to individual portraits of vegetables, such as Adriaen Coortes’ A bundle of asparagus of 1703, displayed in the Feast & Fast exhibition (fig. 1).

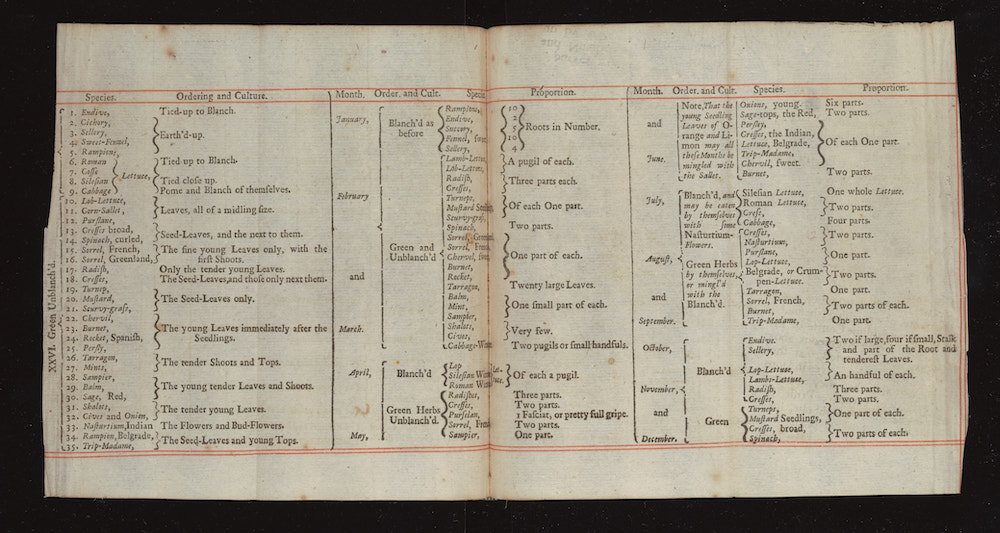

Evelyn’s fascination with vegetables was culinary and horticultural as well as antiquarian. He describes a friend’s gift of sixteen enormous ‘Sparagus’, each weighing a quarter of a pound, which had been grown in the ‘more natural, sweet, rich, and well cultivated Soil, about Battersy’ (Acetaria, p. 165). The combination of gastronomic curiosity, scientific interest, and ancient learning comes together in Evelyn’s discourse on salads of 1699, in which he listed 82 different vegetables, leaves, and ingredients for salads. He also included a chart about their growing seasons and ways of preparing the salad ingredients. This is followed by a 9-step guide for dressing a salad, which shows his practical engagement in the making and eating of the salad, well beyond his bookish pursuits.

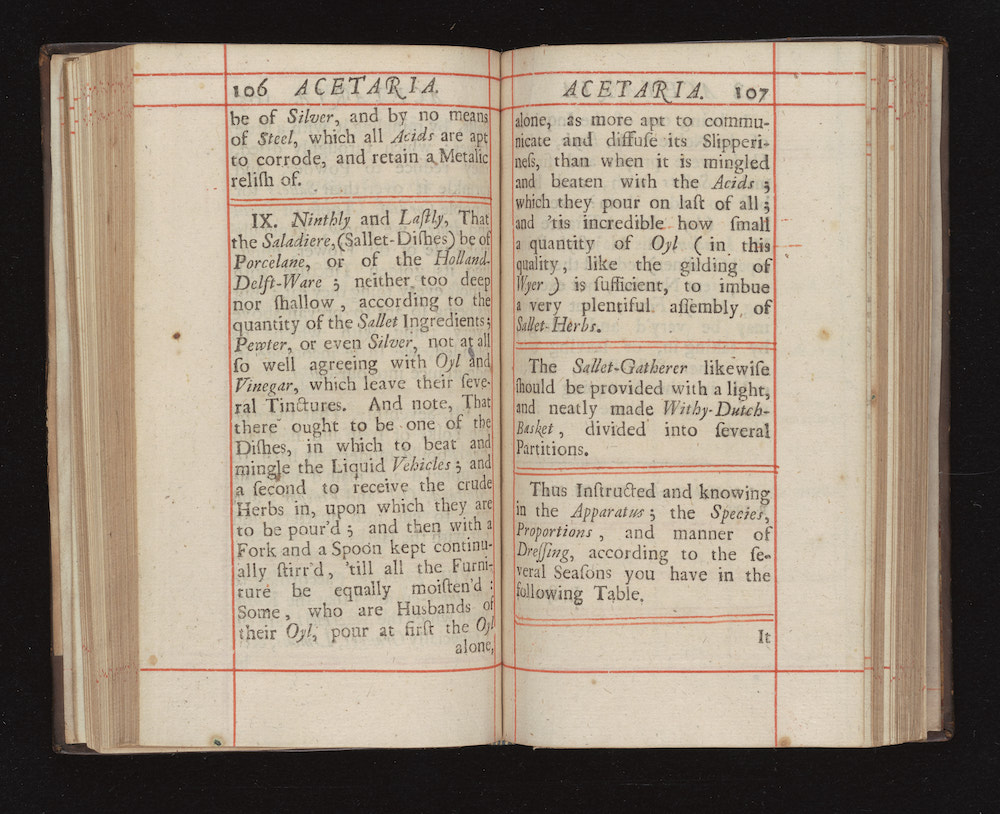

First, Evelyn writes, one must clean ‘your Herby ingredients’, making sure that they are drained of any ‘superfluous Moisture’. Second, ensure that the quality of the oil is ‘smooth, light, and pleasant upon the Tongue’. Third, the best kind of wine vinegar is one infused with cloves, rosemary, roses, or nasturtium. The quantity and quality of salt and sugar to be added are the focus of the fourth step. The fifth step is dedicated to mustard (‘that noble ingredient’), and the sixth to pepper (‘white or black’) and other ‘Strewings and Aromatizers’ such as orange and lemon peel, juniper berries, and saffron mixed with honey reduced to a powder and sprinkled on the salad. The seventh step is the addition of the yolks of boiled eggs mixed with ‘Mustard, Oyl, and Vinegar’. The eighth step advises that the knife to cut the ‘Sallet-Herbs’ must be made of silver to avoid the metallic taste of steel. ‘Ninthly and lastly’, the Saladiere (or salad-bowl) should ‘be of Porcelane, or of the Holland-Delft-Ware; neither too deep nor shallow, according to the quantity of the Sallet-ingredients; Pewter, or even Silver, not at all so agreeing with Oyl and Vinegar, which leave their several Tinctures’.

Evelyn would have known that the 1st Century CE Greek physician Galen had cured his insomnia by eating salads. According to Galen’s theory of the Four Humours, raw vegetables were considered a body-balancing food. Evelyn’s incredibly detailed guide to the perfect salad dressing shows that his interest was motivated as much by his stomach as his mind.